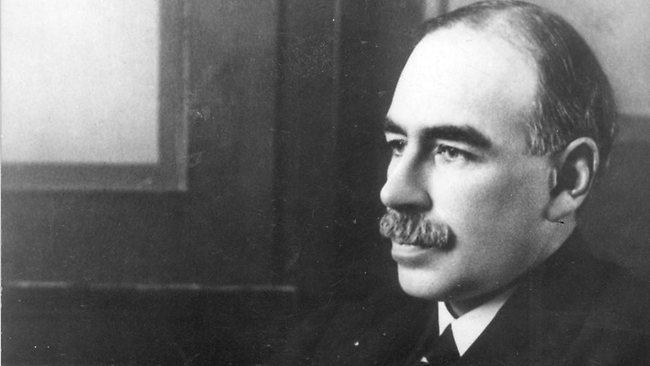

They are simply volume traders. Their nearest equivalent? A taxation gathering authority. This view of banks as providing a public service rather in the manner of doctors or police had powerful origins.John Maynard Keynes for example believed that the replacement of the family proprietors by a new era of professional managers would be a great benefit for society as a whole. Keynes believed that this newly-empowered industrial class of the professional manager unfettered by the need to enrich the hereditary owners would instead devote their talents exclusively to improving the enterprise. Keynes reasoned that in doing so that these non-dynastic managers would also attend to a wider social responsibility for the enterprise.Keynes held this view in spite of the fact that the joint stock banks of his era had been started by and were still controlled during his lifetime by their founding Quaker families. Keynes views transcended the Westminster zone and took hold in the United States. Here, of course the joint stock banks of the era were more of a mix. Some had been founded by families such as the Rockefellers or the John. Pierpont Morgans. Others such as the Bank of America founded by A.P. Giannini had been founded with philanthropic intent.Bankers believe it too. For example Britain's Midland Bank, at the time the world's largest branch banking structure went bust because it believed that th US Crocker bank was telling the truth about its position. It was riddled with concealed debt. HSBC acquired what was left of the Midland.Either way the Keynesian concept of the separation of ownership and management was taken to heart on both sides of the Atlantic. This new era was accompanied by the relaxation post World War 2 of the regulations imposed on the wider banking sector. This trend in the United States survived a number of regional bank crashes and the much more serious savings and loan bust.In the United Kingdom this relaxation of regime not only survived the secondary banking crash of the 1970s, but was much enhanced by it. This was because the industry lifeboat, as it was known organised by the Bank of England, was seen to be a shining example of how the sector managed itself, in this case by arranging its own bail-out.Approaching recent times the collapse and subsequent disappearance of the British merchant bank Barings caused by exposure to what would now be described as casino operations was dismissed as an aberration that could be laid at the door of a single rogue trader.The event though had the effect of reinforcing the Keynesian tenet about the desirability of the separation of the ownership and the management and thus the control of banks. Wasn’t Barings at the time of its crash still under the thumb of the founding family? Look what happened!It was now that the separation of executive responsibility and ownership became a heady brew when it was blended with notions of professionalism conveying an impression that the overriding loyalty was to the organisation as a whole instead of to a small group of individuals and especially so if they held dynastic claims.It was around these times also that the banking culture began to diverge quite sharply from what might have been described as a professional modus operandi. Indeed it can be said up to this point to have had much in common with chartered accountancy centred as it was and is on the minimisation of risk. Instead the banking culture began to be replaced by the now familiar bonus culture in which individual daring was rewarded in the short term regardless of the longer term consequences of the risks embraced.In New Zealand this emerging culture centred on individual achievement became exacerbated by the entry into the banking marketplace of the government, most spectacularly in the form of the Development Finance Corporation. It was interpreted most notably by the Bank of New Zealand as serving notice on the banking sector at large that it needed to embrace risk rather than shun it.In the event the BNZ in its efforts to ginger up its lending to compete with the DFC, as the state venture was known, became insolvent and was absorbed into the National Australia Bank.The Australian banking regulators by now with responsibility direct and indirect for all of Australasia observed this astounding example of the law of unintended consequences. But not before they had organised a limited and silent lifeboat operation of their own to safeguard one of their own banks.Lessons had been learned and the Australian trading banks along with their counterparts in Canada were placed under closer observation. This was not the case on the London-New York axis however. Here banks had ceased to become the servants and facilitators of business. Instead they had become the business. In doing so they had moved out of the purview of regulators in a practical sense.They still are. This is demonstrated by the insistence, even by the bailed out banks, the nationalised ones, insisting on the continuation of the bonus and incentives culture. This in turn is still based on the shorter to medium term results, still regardless of the longer term effects of these rewards which are based on reaching and surpassing sales quotas in an industry that borrows short and lends long.Ethicists are not always welcome in mercantilism. The mission statements and other lofty desiderata that so recently peppered office walls provoked guffaws and reverence in equal measure.The transition though of the banking culture to a marketing culture was a fairly rapid one and can be dated from the 1980s. Its enduring nature is demonstrated in that when its flaws were laid bare it was still impossible to expunge. It penetrated the industry’s mainstream which is why the Basel accords seeking to reduce bank financial cushions took so much effort to be put into reverse, and greater, instead of less, cushioning put into place.Australasian regulators saw it coming and thus averted it. Regulators and practitioners in the United States and Britain even if they saw it coming were powerless to sidestep it. The bankers had slipped from their mooring of the banking culture, the risk minimisation one, and had adopted instead a growth and marketing one. It reminds us yet again how carefully must be used the word profession and that this is especially so if those being referred to have knowingly or unknowingly undergone a transfer to another set of loyalties, another set of standards.Even if bankers wanted to be professionals off balance sheet dealings now more than ever prevent them from claiming to being a profession.

from the MSCNewsWire reporters' desk